You can become what they say you are…or you can be what you chose to be.

If you had asked my maternal grandmother why your nose is itchy, she would have told you it’s because someone is missing you. Itchy palm? Well, that meant someone owed you money. She also insisted that if you ever mentioned any good news or words of good fortune out loud they must be followed by a quick three spits to ward off the evil spirits. I always found this odd because short of those particular spirits, Babushka Genya never spoke of anything else spiritual.

Genya was not an interesting person. No discernable depth to speak of. In fact, I never saw her read a book or a newspaper, never heard her have a deep conversation, never saw her watch the news or take interest in world, local, regional affairs. Her world was filled with the events of the day, cooking and other people’s business. She loved other people’s business so much that she would treat it as her own. She would worry about people’s business, talk about it, try to impart her wisdom, which was rarely wise and even more rarely solicited, on anyone within earshot. She was a busybody in the classic Eastern European grandmother trope. She knew everything about everyone and what she didn’t know she completely made up with the alacrity of a fiction writer who gets paid per word. She knew everything about everyone, but she chose to know very little of the world. She reveled in her unwise wisdom gleaned from the stove, sewing machine, shit stirrer’s pot and running away from Nazis.

Genya’s life was not easy. I suppose anyone born in Tarascha, a southern Ukrainian village roughly 120KM south of Kiev, in 1912, could make that same claim. Her primary language was Yiddish, and she did not learn Russian until she was in her teens when she, along with her mother, brother and sister, moved from the village into the big city to join her cousins, aunts and uncles. The family scraped by. Eventually she got a job as a seamstress in a factory where she met her future husband Michael, a tailor by trade. As the story goes, my grandfather wanted very much to meet my grandmother but being an awkward youth, he could not figure out how to approach her. One day as she was walking past him he decided to trip her to introduce himself. She fell. He apologized. The rest as the say is history. They had 2 children, mu uncle Naum and my mother Sima. Then June 22, Hitler, Babi Yar, evacuation, Tashkent, news of her husband’s death most likely at the hands of the Soviets after the war, slow return to nothing, rebuilding a life.

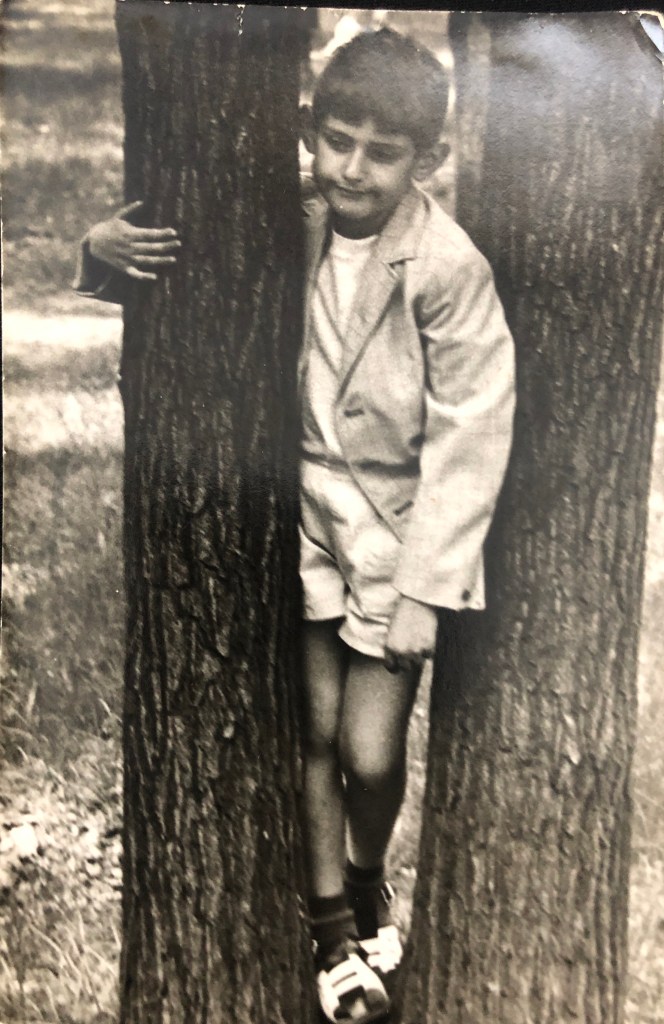

She was difficult at times, she created a never-ending stream of enmity in our family… but she was kind to me and loved me very much. She would always tell me that I was the best part of our family. A distillation of all things positive. “A good, good boy with a clean, clean soul.” (or as she would have said “ Хороший, хороший мальчик с чистой чистой душой.”) Her name was Genya (pronounced with a hard G, as in “Gandalf” rather than “generation”, though in the Ukrainian accent which softens the G significantly as compared to the Russian. A distinction which only matters to those who speak Russian with the eye for identifying the uncouth Ukrainians among them) My birthname was Gennady, with the diminutive “Gena.” Same hard G softened by our Ukrainian pronunciation. I spent countless hours with her as a kid. It was always Genya and Gena. (The American equivalent of Julia and Julian or Roberta and Robert to illustrate the point. To most American ears, however, it sounded like that Saturday Night Live skit where everyone in the uber-euro-chic art dealers house is named Noonie. )

Had you asked my grandmother, she’d have likely told you that a person’s name has an impact on their personality. Every Michael she knew (her husband, her grandchild, her cousins), she would tell me, were very much the same. And, according to her, our names were similar and that meant we were similar people. We were both “Good, good people with clean, clean souls.” I never understood this because when it came to personality she and I were so incredibly different that the phonetic similarity of our names surely could not have meant anything at all. I never believed that names matter…but maybe they do.

I was born Gennady Aronavich Ortenberg. The etymology of the first name is from the Greek “Gennadius” meaning generous or noble. I doubt that my parents ever knew that. The tradition in our family is to name a child after the first letter of a deceased relative. And there are few Russian “G” names. I suppose I could have just as easily been Gregory. As it stands, I was named Gennady after my great grandmother, Golda. I don’t know much about Golda except that she had lots of siblings most of whom died at the hands of the Nazis and that she, along with my grandmother, mother and uncle, was separated from those left alive during WW2. While I am not sure where the rest of the clan was, Tashkent was home to Golda and her brood for 4 years.

My patronymic (the Russian middle name essentially meaning son or daughter of) was always strange to me. Though my father’s legal name was Aron, no one ever called him that. He went by Alec. So, when asked to recite my name, I would often use Alexiavich (son of Alexi) as my patronymic only to be corrected. Alexyovich was significantly easier for me than Aronavich (son of Aron). Aronavich screamed “Jew” and while I knew I was Jewish, as a kid being in the tribe was never high on the list of things I was either proud of or wanted to share. This was my first identity. Gennady Aronavich Ortenberg. Everyone used my diminutive, Gena, or (and there are a few people who still do this largely to my pretend annoyance) Genochka, a further Russian diminutive meaning “little Gena “. This is how my family and early childhood friends knew me. I was born into a Jew in a Russian culture. Outsiders in the greater Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. Russian in mannerisms, clothing and tastes; foreigners in faith, jokes and food. Pariahs in political life, marked as such on our passports, reviled as a people; zhydi, kikes. But we were happy and content, connected and well fed, resourceful and frugal. Just your average middle-class Jews in a sea of Russians and Ukrainians.

The DNA of the Jewish sojourners was deeply engrained in us. Yet as opposed to the Rabinowitzs and Rappaports, who have lived in Russia for generations, whose names were familiar to the Russians, Ortenberg had more of a Germanic tinge. The Jewish Rabinowitzs and Russian Kuznetzovs equally mistrusted the Germanic sound of my last name. I would have much preferred to have had a stereotypically Jewish last name, if only to limit the derision and disgust from just the Kuznetzovs. Ortenberg sounded so German that I scarcely remember ever having the option to play on the Russian side of the “Russians and Germans” make-believe wars. The wars the neighborhood kids played out every afternoon in the courtyard of our apartment building. This was Soviet era kids playing cowboys and Indians, Russian style. And I was always in Wehrmacht. (In my head, truth be told, I always thought I was in the Luftwaffe. Given the chance my arms would be stretched out like a Messerschmitt… pew, pew, pew…the Yakovlev –1’s did not stand a chance!!!)

Being a Jew with a German last name living in Ukraine and being a head taller than everyone my age may be the secret recipe for a lifetime of alienation. I was too young to understand identity. Being a Jew only meant I was not like others, being an Ortenberg meant I needed to accept my role in the make-believe Wehrmacht, being tall meant that I consistently disappointed people who thought I was older. I lived in a grey zone of group identity. Constantly reminded that I did not fit neatly into any group non-distinctiveness which the people around me seemed to wear so completely and comfortably. Gennady, Gena, Genotchka were my identity until a summer day in 1980. In April of that year my family (dad, mom, sis and grandmas) emigrated to the Unites States. We moved into a one-bedroom apartment in a largely Italian neighborhood of Bensonhurst, Brooklyn. My maternal grandmother, Genya, had moved in with her sister Klara who had come to the US a few years earlier. I shared the bedroom with my parents while my sister Maya and Grandma Feige slept in the living room.

The apartment was cramped, lacked any privacy and, given grandma Feige’s atrocious hygiene habits and acute agoraphobia, always smelled as if a construction worker accidentally left their half-eaten egg sandwich behind the sheetrock. Just a subtle smell of barely perceptible, ever-present rot. We were the vanguard of a giant wave of Soviet emigres pouring into Brooklyn and the tip of the spear of those moving into Bensonhurst. In the years since our arrival the largely Italian neighborhood gave way to the Russian wave which later gave way to the Asian wave. As in all thing’s immigrant, the old neighborhood was a stop along the way towards the eventual absorption of the immigrant soul into the broader suburban America. We were fodder for the American dream. We were the tired, the poor yearning to be free or at least have a nice 19-inch Zenith color tv, supermarkets with food on the shelves and the incredible innovation of TV dinners.

At the time of my immigration to the US my entire English lexicon consisted of the following: the numbers 0-10, mother, father, sister, play and football. Ok, the last one was not so much English as universal. But I had a tutor and was learning to understand English quickly. My tutor was patient, inexhaustible and always ready to teach. My tutor had two dials. One called VHF, which had seven channels and a mysterious second dial called UHF where on occasion some pixilated, blurry content would show up. Once, when I was left alone, the mysterious UHF dial showed me naked breasts. I was transfixed and stared at the large bare-chested African woman on the TV. Then I heard a noise panicked turned the channel and left the room. Ten minutes later I returned to the TV to find those breasts but to no avail, the UHF dial was a crap shoot and I all found was boring interviews or static.

The VHF dial, on the other hand, was magically educational. I tended to focus on channel 5, 9 and 11 as those channels had the most amazing education programing; Gilligan’s Island, The Ghost and Mrs Muir, Mr. Magoo, The Munsters. This was significantly better than the midafternoon industrial progress reports I remember watching on our tiny black and white back in Kiev. Most of May and a part of June of that summer were spent watching hours and hours of television. We were the first Russian family to move into this part of Brooklyn. There were no other kids who spoke my language and all of my cousins, who lived on Brighton Beach at the time, were, like my sister, at least 8 years older than I.

After a solid six weeks of 8 or more hours of daytime TV and days with nothing but the ever-present rotten egg salad smell emanating from grandma Feige, I began to be restless. The Jetsons, the Flintstones, The Bradys and the Partridges were great, and they taught me a lot… but I needed to get out of the house. I missed the old neighborhood games, even if I were a dirty German spy. It was better than smelling my grandmother decompose.

I looked out of our second story window onto 21st Ave. A group of neighborhood kids I’d seen a few times before were gathering in front of the stoop of the 3-story house right next to our less than grandiose 6 story apartment building. They were throwing a football around. I had never touched an American football in my life. I don’t know why, but I decided that day was going to be the day that I made new friends.

By the time I made it downstairs the boys had crossed 71st street and we were choosing up sides to play a game of tag football in front of PS 247. I walked across the street and stood on the corner for a minute while they ran their play. American Football was a mysterious sport what with the use of hands and an elongated egg for a ball. When the kids huddled up for their next play I walked over and said, “I want play.” Prepositions be damned, they don’t exist in my mother tongue… and while I tried to deliver the words in my best Keith Partridge coolness and tone I have to imagine I must have sounded a lot more like Boris Badenoff ( who btw has the worst Russian accent with the exception of John Malkovich in Rounders.)

“ I want play”… those three words changed my life. Not because they introduced me to a group of kids with whom I would have extraordinary adventures teeming with lessons which would serve me through my adulthood. No, that would never happen. Because my parents decided not to send me to public school and instead have me attend a newly created school for Jewish emigres from the former USSR, once the school year started I rarely played the kids I had was now trying engage. My life was changed, rather, because the reply to those words from one of the kids was “what’s your name?”

I was Gennady Aronavich Ortenberg, diminutive Gena, …. “Ge” as in “get” sans the T and “na” as in na na na. Ge-na, but with the slight Ukrainian accent on the G which softens it just enough to make it nearly imperceptible to the American ear, especially an Italian-American ear which was more used to Vinnie Barbarino than Ustym Karmaliuk.

“ My name is Gena”

“What kinda name is that”

Silence

“We’re not calling you that”

“I play?”

“You wanna play? “

“yes”

“ok… but were not calling you whatever your name is”

“okay”

“Hold on…guys huddle up”

I’m wasn’t sure what was happening… huddles are a very American football thing. I was not yet an American. Roughly 10 boys between the ages of 10 and 12 stopped playing football and all got into a tight circle. I could not hear what was being said, but I knew it was about me. There are murmurs but no laughing…

I wait.

The huddle broke apart. A kid named Carmine walks up to me with a football in his hand. He lobs it to me and says:

“Your name is John…”

“ok…John..ok.. I play?”

“Yeah, John. You play”

I don’t know what a baptism feels like… but in some sense that day I was reborn and christened John. It would take another 30 years before that name was at the core of who I am. In the interim years I would have another name. One whose etymology was from the Hebrew meaning “sojourner there.” A name which shaped my character.