Yehoshua said: Make for yourself a Rav ; acquire for yourself a friend; and judge every person on the positive side.

It’s a Jungle Out There

Of the many inexplicable things about my parents relationship perhaps the most puzzling was their view on books. I scarcely remember my mother not having a book in her hand. She read at breakfast, during her commute to work, at night as she wound down. She brought books on vacation and would read for hours as a time while she sunbathed her way to melanoma . She would even bring a book onto an air mattress and float out into the Black Sea to read. Considering she did not know how to swim, this was perhaps one of the few times she should have left the book (and herself ) on the beach. She read fiction and nonfiction. Classics and modern literature, translations of authors from around the world. She read Tolstoy, Bulgakov, Lermontov and trashy romance novels. She bought and borrowed virtually any book she could get her hands on. In the first year or two after our arrival to the US it was difficult to find Russian books, but she managed. Nothing would stop her from reading.

The polar opposite was true for my father. I have never, in the 40 odd years of having known him, ever, seen a book in his hand. Not even an instruction manual. No one was going to tell him what to do not even the manufacturers of whatever product he just bought. He knew how to read but preferred not to do so. He never asked my mother what she was reading, showed only derision towards me when he realized that I gravitated towards books and generally seemed completely and unashamedly bibliophobic. Books seems to be his kryptonite and he avoided them at all costs. Instead he preferred television. His favorite shows were the 1980’s detective genre. To him Magnum P.I. and Hunter were the hight of western civilizations contribution to the arts and the The A Team was his Dostoyevski. In some respect this tells you every you need to know about their relationship with the exception of why they ever tied their fates to each other.

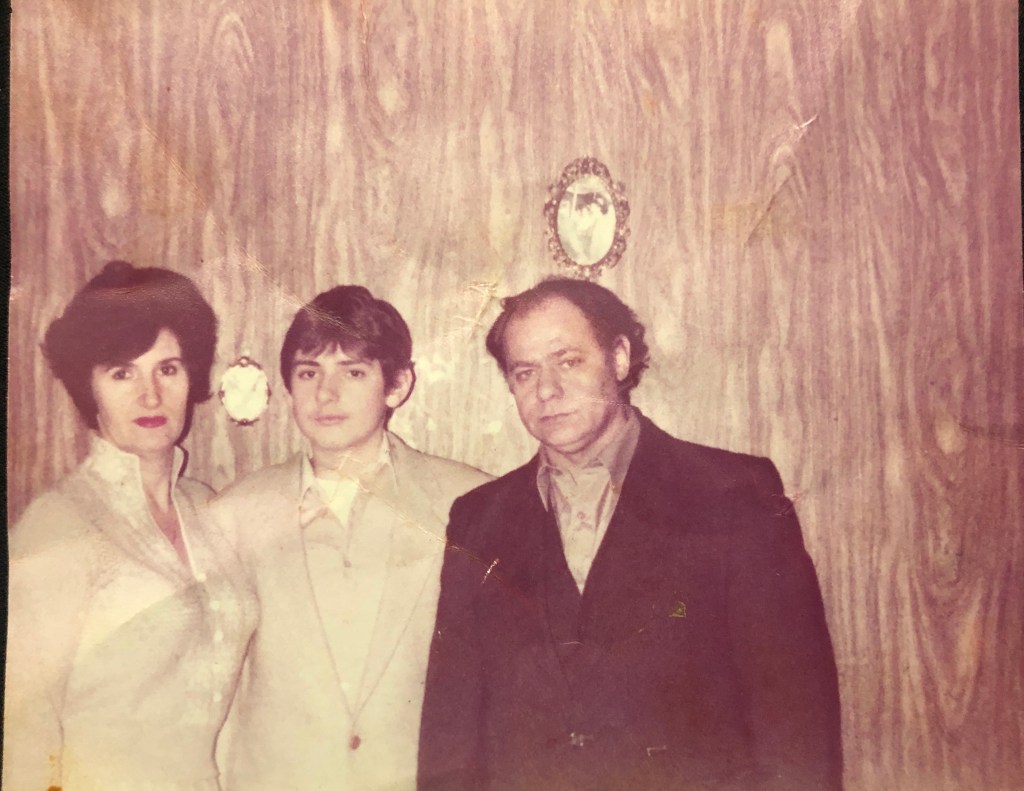

I often wondered how and why these two people, who over the course of their marriage wound up with so much disdain for each other, ever got together. I’ve yet to meet a person who’s ever said ” they are so good together.” Was there a chemistry between them to which I was not privy given my late arrival on the scene? Was there something different in the wooing Aron which was dead in the provider I knew? Some unseen gentleness which withered after the vows were said and reality set in? Had the wooed Sima been so preoccupied by feelings that she could not see for whom those feelings grew? Did they change as people in the same way my own personal growth caused, in part, the dissolution of my marriage? It is far too late to ask those questions. They are both gone.

The first book I clearly remember being read to me was The Jungle Book by Joseph Rudyard Kipling. The book fascinated me. I was no older than 5 when my mother first read the it to me. I was always transfixed by her reading. She sat on my bed and read the story in her velvety voice. She spoke the names of Bhagera, Baloo, Mawgli, Raksha, Akela. Strange names which evoked a far away place with a familiar sense of alienation. I had the vision of Bhagera, sleek and sly, as i imitated the beast during the day chasing Asta, our Alsatian. I wanted to be the panther. I loved the strength of Akela, the leader of pack, powerful and wise, strong and cunning on his rock surveying his pack. Later in the second jungle book Akela fights along side Mowgli to the bitter end. I always wanted to look at my dad that way. But like in the story, father wolf was a minor character and when I tried to think of father as Akela, his face would morph into Shere Khan, the tiger. Perhaps it was my fathers near constant roar.

It was much easier to envision my mother as Raksha, Mowglis adopted mother. Both were loving and protective but fierce when the need arose. My mother bared her fangs and fought violently against an attacker who assaulted us as we were coming home one dark night. Her gentleness, the blanket under which I felt all the possible warmth of the universe, was no where to be seen that night. She hit the drunken man who tried to grab her with furious violence, willing, like Raksha, to defend her son with her life. She pushed me towards the entrance of our apartment building as she faced her attacker. She struck him as hard as she could several times until he, in a drunken state, fell backwards. I was confused but within seconds she was at my side pushing then pulling me towards the entrance. We never spoke about that incident. Perhaps to keep the Soviet crime statistic low.

She also never wavered in stepping between my personal Shere Khan and I when his anger at and frustration with me would elicit murderous shouting and name calling. She never shied away from a yelling match with my father whenever he tore into me, typically over something frivolous. While his ire was ever present, he reserved the worst scoldings to accentuate my emasculation.

He would, on many occasions, invite me to participate in some handy work which needed to be done. I suppose given the gulf in our temperament and interests, this was his way of reaching out. The first few minutes would fill me with elation. Here I was with my father ready to help him with a manly chore. Almost without exception that elation would quickly turn to dread because I would be asked to complete a task for which I was neither trained nor with which I had any experience . “ Here, bang this nail in” or “here is a brush go paint that” that was the extent of my instruction. Invariably my attempts would fail. But there was no gentle redirection or encouragement. My failure as a man must have been seen by my father as an affront to his own masculinity. And just as I was feeling small and useless in my own failure, deflated in my inability to complete what my father clearly thought was a task a moron could handle, the loud words came tumbling end over end into my ear . “Durak, Kazel, Baran, Tupoy, Predurak,” The tool would be snatched away from my hand and I was sent to mama with all the frustration and disgust a lifetime of disappointed fathers breathed into his voice.

Mama’s response was white hot fury. She would unleash a loud verbal assault at my father. Parrying every jibe, every insult hurled at me. She would scream at the top of her lungs for him to leave me in peace and stop saying these terrible things. “who speaks that way to a child… their own child!!!!!!” I took no pride or solace her defense. I would have gladly taken more verbal abuse if they would simply stop yelling at each other. My ineptitude not only ruined the project but obviously my parents marriage.

I hated my personal Shere Khan. But I feared the jungle without him more. The idea that mama and papa would separate scared me more than all the insults put together. As far as I was concerned this was normal and not so bad. After all, things were worse for others. My Shere Khan never hit me. He never tried to eat all of me, just my soul.

Perhaps its mere coincidence that this is the first book which I remember being read to me. Perhaps I remember it because in some ways parts of this story resonated with me throughout life. Like Mowgli, I never felt the sense of home. Of belonging to a pack. The perennial outsider, I was the youngest of all the cousins, the tallest of all my classmates, the gentlest of all the boys in the yard, least mature than all my kindergarten playmates, more interested in the feminine that all the boys I knew, more introverted than a boy was expected to be and lonelier than I wanted to be. Mowgli fought for and got his acceptance of his pack. I, instead, chose to leave the jungle. My initial exit was not physical but rather the rejection of every thing which tied me to my pack. My parents aided me in this unwittingly.

For some unexplainable reason they sent me to Yeshiva Be’er Hagolah who’s pedagogical efforts were squarely aimed at lighting the lord’s truth in the embers of Soviet Jewry by making more Orthodox Jews . While deeply non religious my parents sent me to a school which eschewed the more esoteric and spiritual forms of Judaism for the constraining confinement of orthodoxy. This was not the ethereal, wispy Judaism of the reform who are more concerned with the sense of the community than with the literal interpretations of archaic laws of Moses, nor was this the middle of the road conservative judaism which startles the fence between hard line orthodoxy and its reform distant cousin. No, this was the no electricity on Shabobs, can’t wear linen and wool in the same garment, the only reason we don’t kill adulterers is because the temple is not standing, separate meat and milk dishes, don’t touch the opposite sex, TV and Radio are the tools of the devil, we are better than everyone, Judaism.

By day I was subjected to the never ending rules and regulations of the talmudic faithful being explained in all of their tedious detail. With barely any real command of the english language, I was taught to read and write the Abrahamic texts, say the prayers and adopt the customs of the Chosen People.

The plasticity of the human brain is impressive. It allows for a child of 9 to absorb and process the simultaneous acquisition of multiple languages while also learning mathematics, history, science and the Pentateuch. What it cannot do well is deal with the cognitive dissonance of learning about the wages of the sin of eating “traif” at school and being served pork chops before homework.

My confusion grew because I had no way of reconciling Judaism which I knew with the one presented to me at school. My judaism, the one everyone I knew practiced in the USSR (and now in America,) consisted of a few speciality dishes our regular celebrations. Gefilte fish and Kishke were the Jewish accouterment at the celebration tables next to the cholodetz ( gelatinized pig trotter) and pork roulette. If that did not make you jewish what did? We even used fresh carp for he gefilte fish like Moses’ wife must have. The fish would spend a few nights in the bathtub awaiting their contribution to our Judaism.

There were words like Pascha (passover) and a lot of Yiddish spoken in the house. Most of it when secrets were told. I only learned the fun Yiddish words… Drek, Gey Kakken… Our Judaism refereed to non jews as Chazer ( pig), our judaism referred to our brethren as lantzmen, our judaism prevented us from getting the best jobs and got us called Zhyd.

But this new Judaism I was being taught was prayers and no cheese on bologna sandwiches, it was women teachers with covered hair and endless groveling in front of god, reading backwards with dots under letters, 24 hours without television, songs I did not understand, getting my foreskin removed, men wearing shawls and boxes on their heads, waving chickens around, throwing bread at water, holidays that lasted for 7 days. It was overwhelming. But it was also not of my pack and as such it made it more attractive than anything else. I needed little encouragement to embrace it. I just needed a teacher.

Rabbi David Riess was the first teacher who told me that I was smart. To him smart meant that not only was I able to pick up reading Hebrew quickly, I was also grasped the concepts he was trying to teach. He saw that my mind was quick and hungry. I soaked up knowledge and ideas, especially funny Jewish ones. I grasped the meaning of the text and was able to quickly articulate the spirit behind it. I connected the dots and soon did not even need them under the Hebrew letters.

Rabbi Riess was a man who suffered no fools. An imposing 6’3” with a thick beard and large frame. He spoke with authority but not of the rabbinical high and mighty type. His voice boomed. And he said “fogetaboutit” better than the Italians. His physical presence was as intimidating as my fathers. Even more so.

He knew his audience, young lost kids just arriving in the United States who had no concept of what a Jew was. He was an all American kid who believed in the sanctity of his god and the righteousness of his cause but without an ounce of expectation that his students would feel the same, for now. But he demanded your respect for the Torah and God. He demanded and got the respect for the word of the lord. He knew how to crack a joke and make fun of the other Rabbis in the school for being too zealous. He knew bullshit from a mile away, and called it out. The bullshit of students who didn’t care and the bullshit of the administrators who did not understand their student body. He valued intellect and integrity and exuded both.

The Rabbi cared about his students first and foremost. He cared about their souls. He genuinely believed that it was his solemn duty to connect with the students and give them an ounce of the Yiddishkiet he knew to be the true path of the Jew. He had no expectations that his students would become themselves Rabbi’s, but if they knew the what to do in a shul, if they knew how to put on Tfillin, if they said the Shema, then he would have done right for the lord. I have known his man for 40 years and he he walked the walk. His righteousness is as undeniable as his humanity.

One day he sat down with me to learn the Chumash (Pentateuch) and was impressed by my ability to learn and recite the biblical stories. As I sat next to him he put his hand on my shoulder and said “You’re a really smart kid.” And for the first time in my life I felt the validation I had been searching for from a man. I found my Akela. His customs were strange but I would leave my pack to join his, if not physically yet, then culturally.

Brilliant!!!!

LikeLike

you are a really talented writer (spelling mistakes and all 😂), I hope you will find a wider audience for your writing. Did you send a copy of this story to your Rav? This kind of acknowledgment means the world to teachers – please do, if it’s not too late.

LikeLike

Thank you Lily. I am terrible at editing. I try, but it’s just not my thing. I went to see my Rav a few months ago. He is suffering from dementia. But he recognized me through the haze. It was beautiful

LikeLike